Sculpture Bête Malzieu

Sculpture Bête MalzieuFrom June 30, 1764 to June 19, 1767,

A beast with a vast hunting territory

These attacks took place in a vast territory which today covers the French departments of Lozère, Cantal and Haute-Loire.

From the outset, these events will take on a considerable scale due to international media coverage without equal at the time!

Engravings of the Beast are published everywhere, from Paris to San Francisco!

Why such an impact?

Why did the Beast of Gévaudan become so famous throughout the world?

This was not due to any role that Gévaudan might have played in the life of the Kingdom of France.

It was a relatively poor land for livestock farming and of negligible strategic importance.

The north of Gévaudan where the Beast rages is separated between the Aubrac plateau and the Margeride mountains.

Far from being as wooded as it is today, this vast territory consisted of moors and grazing meadows dotted with copses and a few sparse forests (Mercoire, La Tenazeyre, Bois de Pommier, etc.).

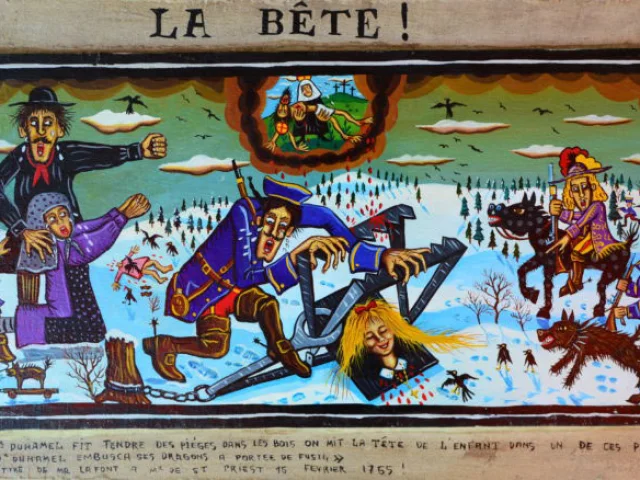

The violent events, which took place in a harsh and isolated region, greatly fuelled the imagination of chroniclers of the time.

For it was indeed the press that explained the scale of this affair.

The end of the Seven Years’ War* left a gaping void in the editorials of the newspapers, until the Gazette d’Avignon took over the affair.

Its editor skillfully embellished the rather deficient news that came from the field.

This media pressure pushed the king,Louis XV of France, to action. Discredited by the loss of the conflict, he must affirm his ability to protect the Kingdom.

*The Seven Years’ War opposed France allied with Austria against Great Britain allied with Prussia (1756-1763).

Moreover, the influence of the Choiseul family was decisive in this case.

Indeed, while Duke Etienne-François de Choiseul was the King’s closest minister, his cousin is none other than the Count-Bishop of Gévaudan: Gabriel-Florent de Choiseul-Beaupré.

In a text that has remained famous under the name of the “Mandate of the Bishop of Mende“ (31 December 1764), he describes this ‘Beast’ as a divine plague and therefore gives a mystical dimension to this affair.

As the representative of temporal power, the Count-Bishop ensured, through his services, a follow-up in the hunt, the dispatch to Gévaudan of the King’s “porte-arquebusier” (=harquebus bearer) to command the hunting campaigns was undoubtedly linked to the close relationship between the Count-Bishop and his cousin, the King’s minister.

During this period, numerous hunts were organised and, among the large number of wolves eliminated, two large canids were killed.

The first by the porte-arquebusier François Antoine on September 20, 1765 at the Bois de Pommier then a second by Jean Chastel on June 19, 1767 at the Sogne d’Auvers.

The death of this last animal definitively put an end to the attacks of the “Beast” in the region.

Gabriel Florent de Choiseul-Beaupré, évêque de Mende de 1723 à 1767

Gabriel Florent de Choiseul-Beaupré, évêque de Mende de 1723 à 1767Why is there such mystery surrounding the ‘Beast’?

Once the Beast had been killed, it was taken to Besque Castle, the residence of the Marquis d’Apcher, where, after being duly measured, it was poorly stuffed and then put on public display for more than a dozen days.

The Beast’s remains were then sent to Paris to be presented to the King.

However, the remains of the animal, which had been hastily stuffed, had suffered greatly during transport and from the heat.

It had lost its fur and gave off a sickening stench when it arrived in Versailles in early August 1767.

The naturalist Buffon, who was tasked with examining the Beast, left no documentation on the subject.

The Beast was never presented to the court. It was neither preserved nor buried in any known location…

Only the testimony of the Marquis d’Apcher’s servant, ‘Gilbert’, who was responsible for transporting the Beast to Paris, mentions a comment by Buffon who, after examination, ‘…judged that it was nothing more than a large wolf…’ but there is no written record by Buffon to corroborate his statement.

This was enough to spark and amplify the mystery surrounding the Beast.

Since the 19th century, this story has fuelled many tales.

Even today, it still crystallises passions between those who believe it was a wolf and the many who hold other theories: man, an animal trained by man, a conspiracy, divine will…

The story and its legend are also a source of artistic inspiration, with plays, novels, comics, movies and more.

The locations are still there,

even if the landscape is much more wooded than it was back then,

Why don’t you also follow in the footsteps of the Beast?

Reference works:

- CHABROL Jean-Paul, La bête des Cévennes et la bête du Gévaudan en 50 questions, Editions Alcide, 2018.

- MAURICEAU Jean-Marc, La bête du Gévaudan: Mythes et réalités, Éditions Tallandier, pp.624, 2021

- MAURICEAU Jean-Marc, La Bête du Gévaudan, la fin de l’énigme ?, Editions Ouest France, 2015.

- MAURICEAU Jean-Marc, La Bête du Gévaudan, Larousse, Paris, 2008.

- MAURICEAU Jean-Marc & MADELINE Philippe, Repenser le sauvage grâce au retour du loup : les sciences humaines interpellées, Presses universitaires de Caen, coll. « Bibliothèque du Pôle rural » (no 2), 2010

- SOULIER Bernard, Sur les traces de la bête du Gévaudan et de ses victimes, Editions du cygne, Paris, 2011.